Deep Listening for landscape design with Usue Ruiz Arana

Architect, researcher and academic Dr. Usue Ruiz Arana's work centres the sonic in urban design, and asks us to listen more closely to the soundscapes we compose and experience.

I first came across Dr Usue Ruiz Arana’s research at an event in a small gallery space in Dalston called Microscope in June 2024. It was the launch of her new book Urban Soundscapes: A Guide to Listening for Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, and sounds from the street outside - cars passing on Kingsland Road, people chatting at the wine bar next door, the rhythmic clacking of stolen Lime bikes - were bleeding in through the open window.

In doing so, these sounds were making a point for the urgency of Ruiz Arana’s work, which emphasises the value of affective, embodied listening in the way our cities are designed and experienced.

Or as her introduction succinctly puts it: “The guide invites landscape architects and urban designers to become soundscape architects and offers practical advice on sound and listening applicable to each stage of a design project: from reading the environment to intervening on it.”

Another thing that drew me to the work that day was the breadth of disciplines represented in the room. Ruiz Arana may be a landscape architect, researcher and lecturer at Newcastle University, but she was fielding questions from educators, engineers and artists alike. It felt like a live space for interdisciplinary discussion - where policy meets practice and chartered acoustic surveyors were taking notes from the teachings of experimental composers.

One such composer is Pauline Oliveros, whose Deep Listening practices have been an inspiration to me (and of course countless others), working in the composition and appreciation of music. When I finally got hold of Ruiz Arana’s book, I was excited to see Oliveros’ approach to listening threaded through her approach to landscape architecture. Exploring sonic methodologies - such as soundwalks and auralisations - are key to Ruiz Arana’s writing, both to offer new skills for practicing architects and to attune us all to the particularities and materialities of our sound environments.

I was thrilled then when Usue Ruiz Arana agreed to answer some questions about her work for Through Sounds, opening up her thinking on a wide range of topics, some quite literally concrete, others a little more ephemeral - from pedestrianisation and acoustic refuges to sonic gentrification, memory and multispecies soundscape design.

I love this notion of a “soundscape architect” and your proposition that “landscape architects and urban designers are soundscape composers”. Could you give an example of this composition in action?

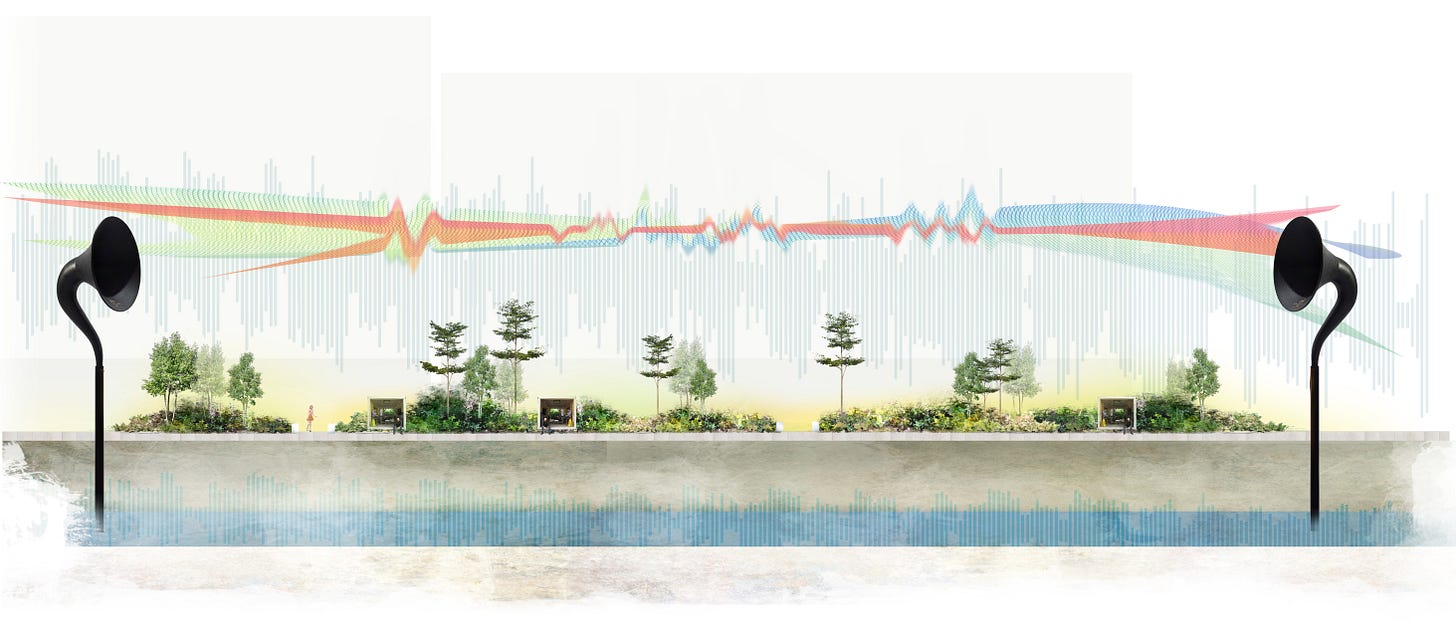

Landscape architects and urban designers compose soundscapes, whether consciously or not, through the spaces that they create, and the communities and uses that those spaces nurture. Communities and uses are sound events, as are the morphology and materiality of those spaces that in turn determine how sound travels within them.

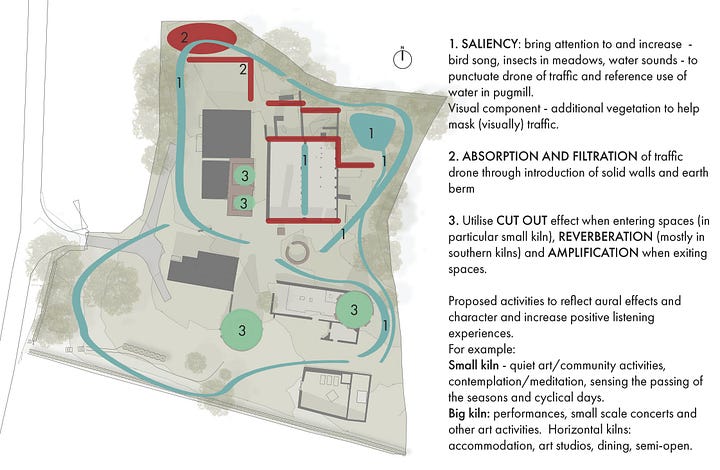

When designing the public realm of a neighbourhood, for example, we can avoid constant hums by keeping car circulation and car parking to the perimeter and encouraging pedestrian-priority streetscapes. Within these streetscapes we can craft spaces for informal play and socialisation that lead to a vibrant soundscape of voices that connects residents to their environment. We can introduce planting to soften hard surfaces and minimise reverberation, and to increase biodiversity and their sonic expression. We can orientate buildings and street furniture, such as low walls, to create acoustic refuges or quieter spaces. We can provide a variety of surfaces to step on and sound. The possibilities are endless, and can really make a difference to how those spaces are used and valued.

In that regard I was excited to see composer Pauline Oliveros appear throughout the book too. What inspires you about her work and to what extent are the practices you set out for architects and designers analogous to those she set out for composers in Deep Listening?

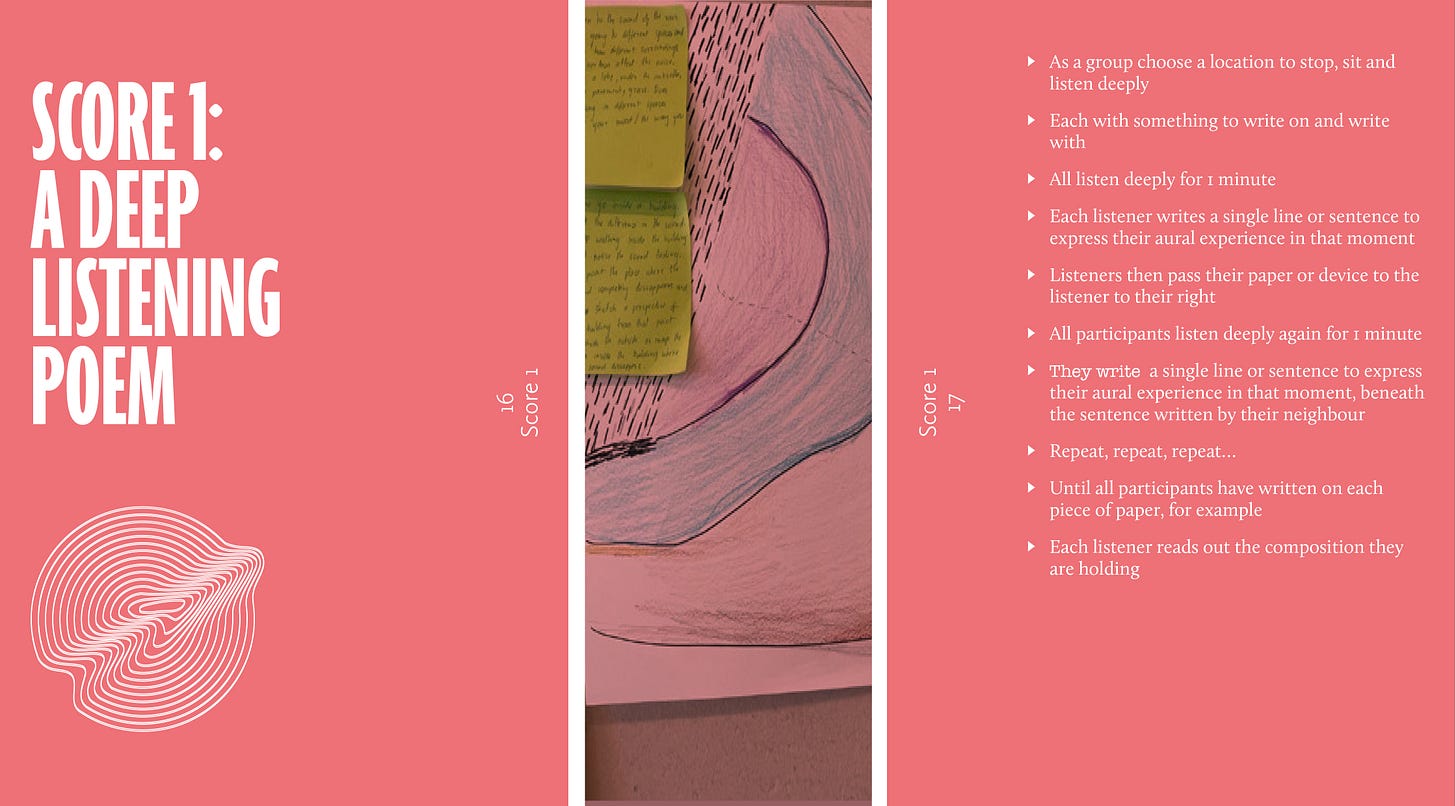

One of the aspects that attracted me to Pauline Oliveros work in the first place, as a landscape architect, was her understanding that anyone could be a composer and a performer, making music and sound art accessible and inclusive. And that proposition is so valid when thinking about urban soundscapes that are composed by a multitude of communities. Deep Listening can be a way of actively involving communities in designing urban soundscapes through the production and performance of written scores, for example.

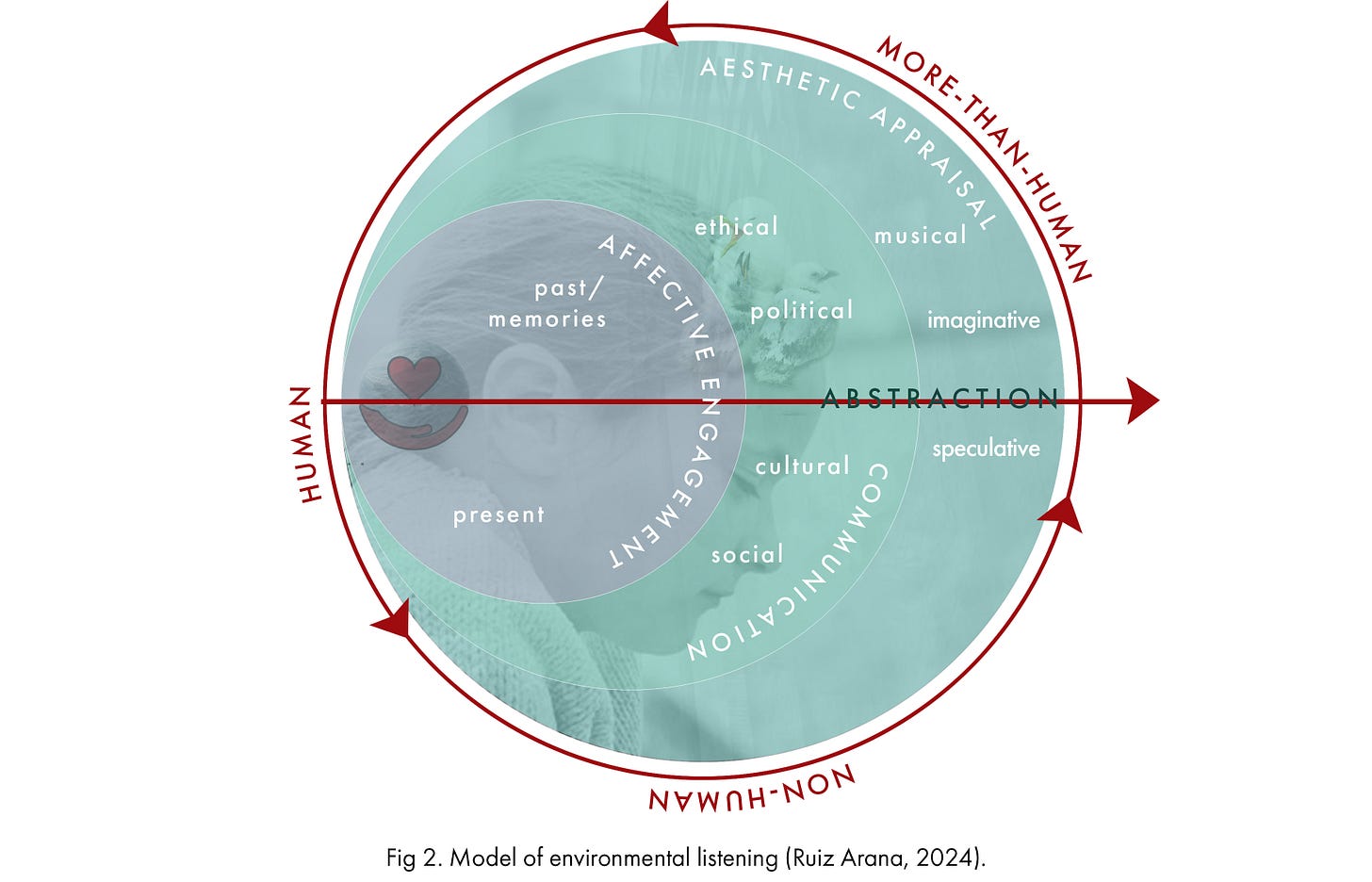

I have been delving into Deep Listening more recently, completing an intensive course with the Center for Deep Listening at Rensselaer, which has made the connection with the design practices that I advocate for even more apparent. A focus on Deep Listening leads to care-full landscape architecture and urban design processes and approaches. For example, the two modes of listening, focal and global, that Oliveros proposes can be integrated into practices for reading soundscapes as a starting point for intervening on them. Through focal listening we pay attention to others and acknowledge their presence and contribution to landscapes. Through global listening we immerse ourselves in landscapes and design from the myriad of connections that we sense in the process, more care-fully.

In her book Quantum Listening, Oliveros talks about Deep Listening as “exploring the relationships among any and all sounds, whether natural or technological, intended or unintended, real, remembered or imaginary”. How could landscape architecture and urban design engage with these more intangible sounds in particular?

Landscapes, whether urban or rural, are made up of many layers - physical, cultural, and natural – that are constantly evolving. Some of those layers are visible, palpable, audible, such as the vegetation of a site. Some others are intangible, held within collective associations and memories of places, or as possibilities or imaginaries. Sounds are intrinsically linked to those intangible layers, and listening enables us to decipher them. For example, sounds can trigger specific memories and associations, which might be helpful to bring attention or express the historic layers of a site. There is an example in the book of a project in Glasgow, the high street Goodsyard, where we used sound as a way to connect communities with a culverted and forgotten burn that played a key role in the development of the medieval city. In the book I also introduce several aural effects associated with memory that can be useful for design.

The introduction to your book begins with your own sonic memories of places from your childhood. What is it that makes these memories so evocative?

We have all cried to music, and responses to soundscapes can be equally emotive. Soundscapes can trigger memories and instantly transport us to places, times, and people that we feel deeply connected to. Some of those connections might be individual, based on live experiences, such as the underwater listening that opens the book. Some other connections are collective, ingrained in particular cultures, such as the soundscapes created by local events or soundmarks that I narrate. These intangible place and culture connections that soundscapes can trigger have a place in landscape and urban design.

Since the book came out, I have been heartened by how these sonic memories have awoken others in readers, particularly in acoustic engineers, who perhaps focus more on technical aspects in their daily work and see an opportunity to expand into more creative and affective sonic methods.

How would the built environment sound if it had been designed by thinking with our ears rather than with our eyes?

Such an interesting question. More varied, for sure. A way to imagine what it would sound like is to think through urban planning decisions that have not been made through ears. For example, mixed-use developments that haven’t considered or addressed in their design the sonic consequences of mixing residential with commercial uses. Or streetscapes where cars dominate leaving little space for community uses (human and non-human) and their sonic vibrance. Or parks covered with pristine lawns devoid of food for pollinators and their buzzing. I hope one of our readers takes up the challenge of crafting such a soundscape!

Why do you think it is that noise pollution is still not taken seriously as an environmental stressor? And more specifically why have landscape architecture and urban design practices also tended to avoid addressing it?

There is a political and economic dimension to why noise pollution is still not taken seriously. In the introduction to the book, I describe the plights of neighbours in Hondarribia [in Spain], who are unable to sleep in the summer due to the active and long nightlife. Tourism and nightlife contribute greatly to the economy of the city and are currently prioritised in decision making over the neighbours’ right to rest. This is just but one example of decisions that are not made with ears. We also do not have the resources in place to monitor live sounds across cities. Noise policies require noise maps to be produced and measures to be implemented based on them, but these maps are static and only capture certain sound sources. That said there are some great citizen science projects happening across the world geared towards collecting live noise pollution.

As a society, we also take noise pollution as inevitable, a consequence of living in urban environments or close to industry. This might well be because we don’t fully grasp the health and well-being effects of continuous exposure to noise. It is a less tangible polluter than others, yet it affects not only our hearing but also our quality of life and longevity, and that of other species too.

I wonder whether there is an element to this debate about the fact that we all listen differently, and experiences of noise are highly subjective. How do you navigate the question that “we do not all hear equally” when designing urban space?

I experience diverse listening through my own kids and their reactions. For example, in my hometown back in Spain, where there are many street celebrations that gather many people and can get quite noisy, my youngest really suffers whereas my other two kids are not troubled by it at all. Having acoustic refuges nearby to retreat to if needed can be very useful in those situations. We all hear differently, and our hearing evolves in time. A key element for the design of inclusive urban spaces that enable multiple listeners to understand and explore those spaces is to engage diverse communities in the design. Community engagement can include soundwalks to assess existing soundscape and active involvement in projecting how places will sound like in the future through co-production of auralisations for example.

Sound and silence also have social and class connotations that are governed by who or what is allowed to make or demand it. How can design intervene in the relationship between sound and gentrification?

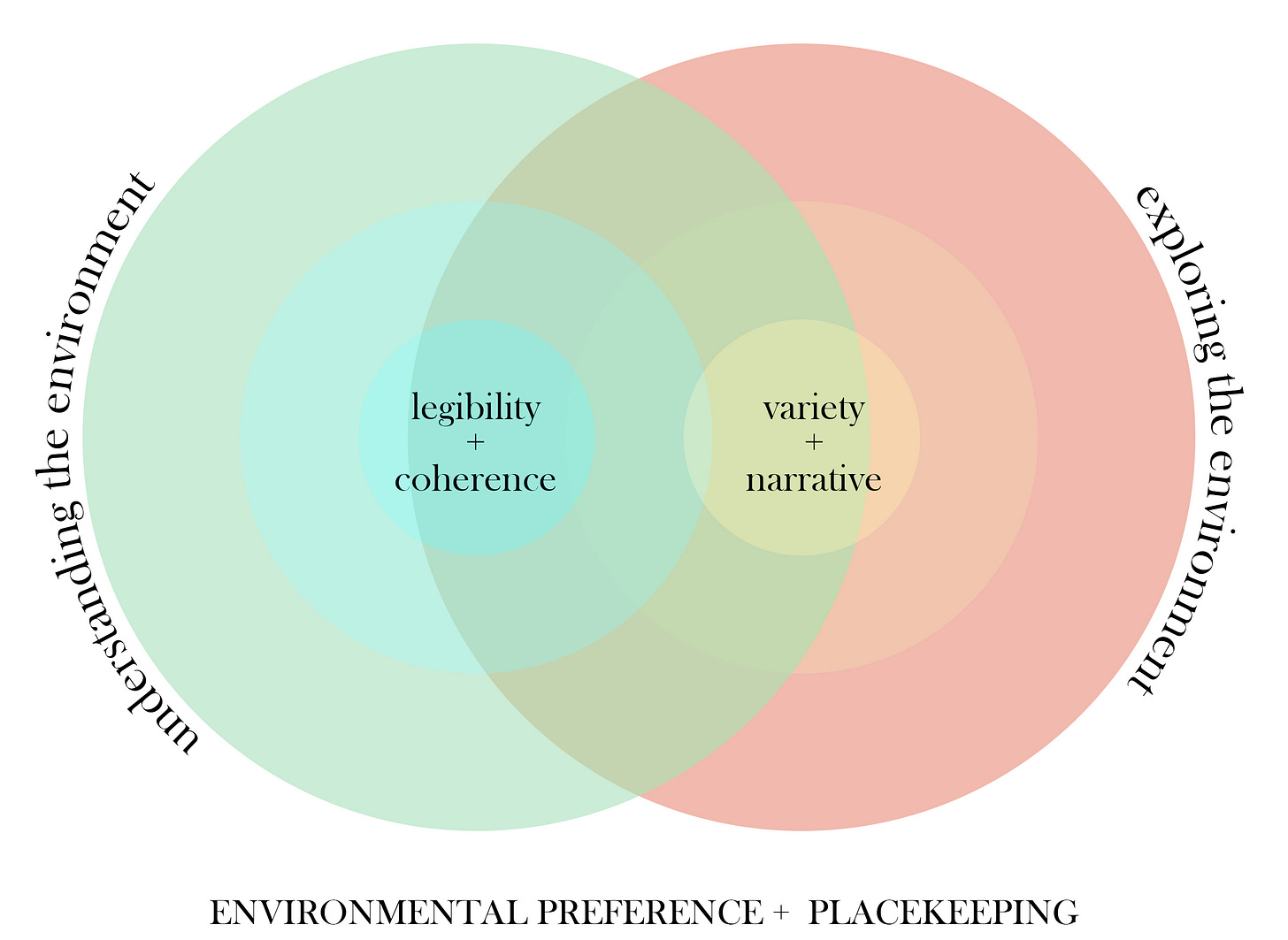

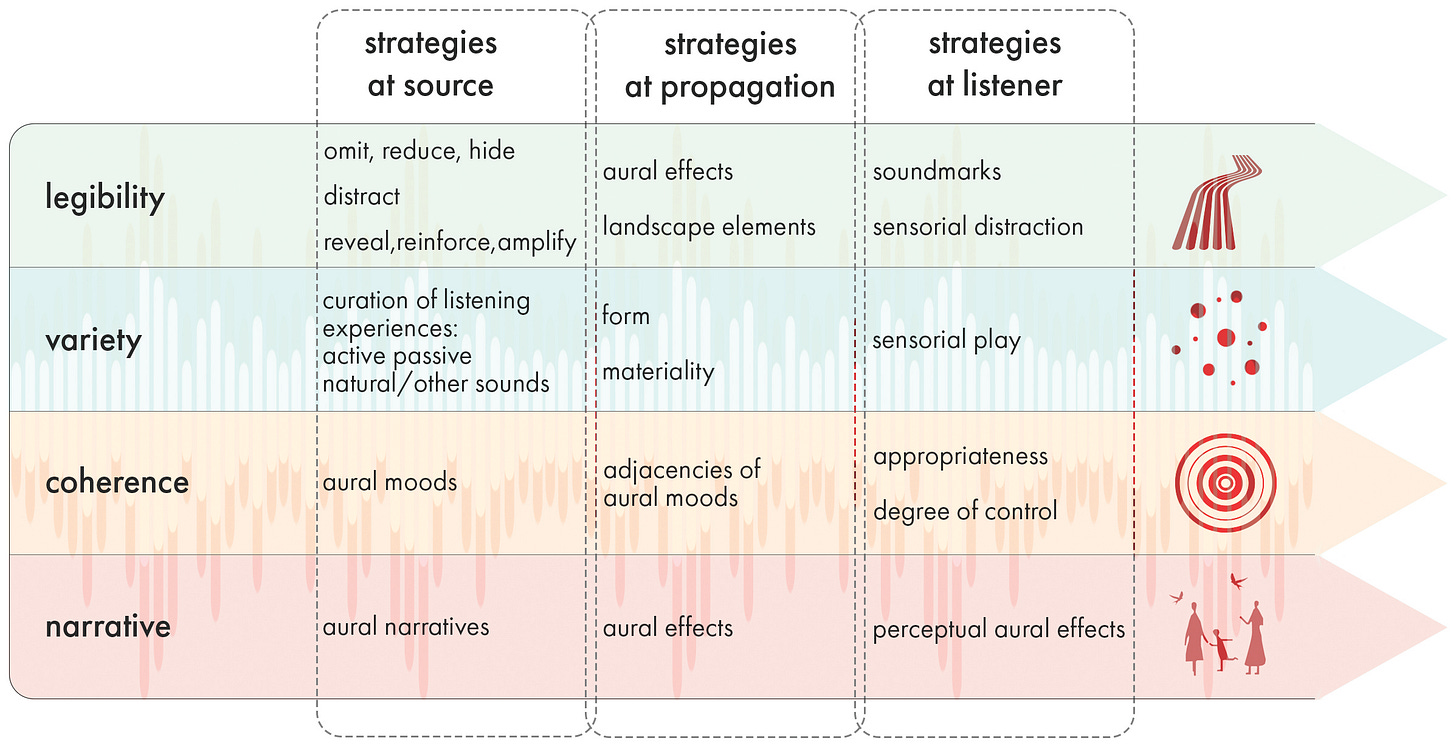

Urban spaces can be designed to be inclusive and accessible to all communities and sound can contribute to how welcomed people feel in the public realm. In the book I introduce four principles for soundscape design that are key for understanding and exploring environments and can play a role in preventing gentrification: legibility, coherence, variety, and narrative.

Legibility is linked to way finding and coherence to how the different elements of the environment can be read as a whole. Making places accessible, that is, avoiding barriers to their use, is key to both legibility and coherence, and some of those barriers might be sonic. For example, sonic interventions have been employed to deter homeless people sleeping at night, displacing them. They are also used to deter a variety of animals. Ensuring spaces, as they evolve, remain connected with people’s daily routines and homes is also key to their legibility and use, and soundmarks can be helpful to that end.

To take this one step further, how does one begin to integrate non-human health into soundscape design?

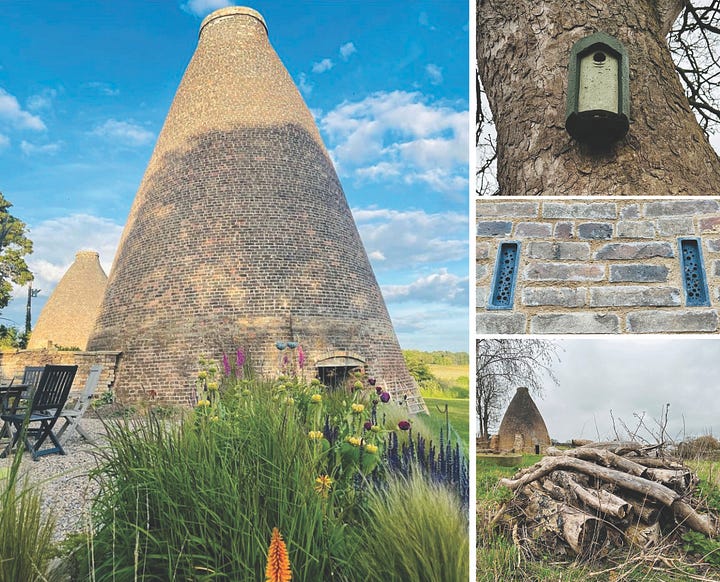

It requires a nuanced approach to design that acknowledges diverse, species specific ways of listening, sensing, and responding to sound. For example, whereas low frequency sounds stimulate growth in certain fungi, they can also impair bird communication. So, there might be competing needs that need assessing and addressing.

Integrating multiple points of listening or sensing into soundscape design begins with an in-depth understanding of the species inhabiting a place and their particular responses to existing and prospective sounds. And it ends with a holistic approach that considers how to best cater for all species across a site and for certain species within a specific habitat or area according to species distribution.

Whereas multispecies soundscape design is complex, it is also a very exciting area for research and development, and one that I am currently exploring with colleagues in different fields and landscape architecture students. The fields of animal communication and ecoacoustics are developing rapidly and we are increasingly gaining an understanding of how sound affects individual species. We should also seek to embrace more-than-human participatory approaches to design that might enable us to grasp subjective responses to sound. Again, an exciting area for future development where collaboration amongst disciplines, including ecologists, artists, and designers, will be key.

Usue Ruiz Arana’s Urban Soundscapes A Guide to Listening for Landscape Architecture and Urban Design is published by Routledge and is out now.