Rob St John records the ecological intricacies of Örö

Artist, musician and writer Rob St John discusses his experiences listening for human and non-human life on the former Russian and Finnish military island of Örö.

Rob St John is an artist, musician and writer interested in the blurring of nature and culture in contemporary landscapes. Earlier this year he released Örö - an artist book, 7” single and short film with Blackford Hill, drawing on his time spent on the Finnish island of the same name. A former military site first owned by Russia and then Finland, Örö had been closed to the public for 100 years before it came into the possession of the Finnish National Parks agency with the intention on turning it into a destination – or what St John calls “military ruins as modern tourism”.

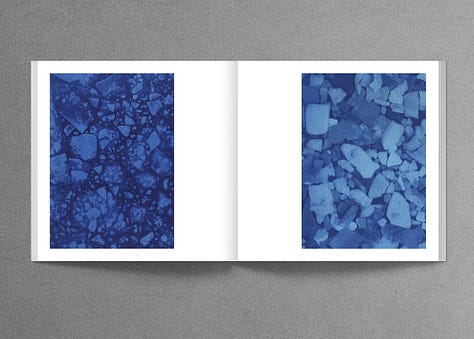

Taking part in a residency programme on the island in the intervening period, St John visited twice – first in deepest winter, and then again at the height of summer, where the hours of stifling darkness had been replaced by near 24-hour sunlight. Using methods borrowed from the academic fields of biology and geography such as transect walks and sample squares, St John gathered visual and sonic material to tell nuanced stories of the island at different ecological, geographical and historical scales.

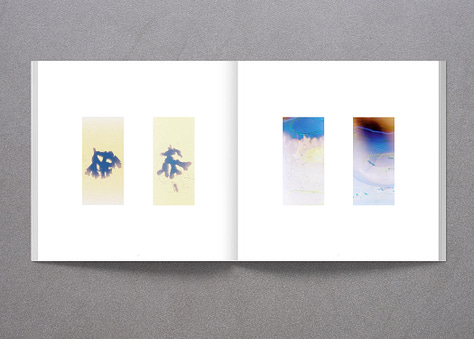

Working with field recordings, hydrophones, contact mics, data sonifications, and granular synthesis, the film and sound works offer his glimpse of a place where nature and human activity are in constant negotiation.

How did you come to be on Örö to begin with?

Örö appealed because a lot of my interests as an artist have been in these very muddled contemporary landscapes, where you get human and non-human, built and organic forms and processes all slipping in and out of one another. I think it's in those places that we can tell interesting stories about Anthropocene landscapes, and the inter-relationships and co-dependencies with which we can think about different futures. When I found out about this weird and wonderful island of all these crumbling structures and resurgent biodiversity, it seemed like a good place to experiment with.

The residency process was really interesting because they wanted an artist on the island in that transition period, and so I managed to get an initial month in January 2016 to go there. I didn’t really know what I was getting myself in for. It was really cold, really dark, felt so remote and you stayed in this converted military barracks house. That first month was a real challenge because I'd taken what you might term a tool kit of cameras and sound recording gear, but there was only very limited amount of light every day, it was very cold, and batteries ran down very quickly.

The combination of military ruins and resurgent biodiversity reminds me of this idea of the military-pastoral complex. What is it that particularly interested you in this?

In coming to Örö, it wasn’t an intentional thing of wanting to think with former military sites. But I do also think they’re really fascinating aesthetically, in terms of these built structures that are very much shaped by the landscape and geology and outlook and weather. There are all these subtle architectural detailings that are to do with command and control and mastery over the landscape, even though they themselves are shaped by what the landscape is letting them do.

And then I think the potential trajectory of where a landscape goes is probably my main interest in places like this. That openness to change and flux and possibility in how landscapes develop. I'm also interested in that in my own art practice and try to find processes that let me channel uncertainty and chance. How much can we guide landscapes towards what we might want them to be, and how much do we need to cede control? You see that in rewilding debates all the time. And I think it was this muddle of historical and archaeological and ecological elements on Örö as much as the military element itself that interested me.

Is that notion of controlling or ceding control of a landscape where this idea of patterning comes from which you refer to in the book? Of patterning the landscape through industrial and human processes but also in the natural patterns that resist it…

That’s exactly it. I became quite interested in thinking across those two categories. When you find visual and sonic resonances between patterns in built and organic worlds, what aesthetic strategies let you think across those categories? What happens when you look or you listen across these different worlds and are there new possibilities and new spaces for thinking, imagining and telling stories from that?

You first went to Örö in winter, and then again in the summer. Was there a difference in the way the island sounded at these two times of the year?

In the winter the island was very quiet. A thick blanket of snow, most of the sea around it was frozen, it was very deadened sound-wise, an occasion crow or buzzard. I spent time with hydrophones under the ice and got some OK recordings, lots of creaks and sloshes and things like that. I spent quite a lot of time putting contact mics onto fence wires that were strung across the island, getting lots of drones and crackles, and also I'd find my way into the empty and derelict barracks, for nothing else than that they looked a tiny bit warmer, and put the contacts on various surfaces as well. I had a little violin bow with me, so I'd be bowing the fences but I’d also go in a bow nails that were used for coat racks, and I suppose because there wasn’t a lot of sound available to human hearing on that trip that it became really a thing of trying to create your own sound palette from the objects and materials that were available on the island. So just lots of play really, very frozen play.

I knew I needed to go back again and that's why I went back in the summer, because I knew that for all that it was a really interesting experience in the winter, I hadn’t made enough sound and film to make the work that I wanted to make, but I also knew that that was only a very partial view of this island and I could have come away with a very arrow perspective on it.

So I came back in the summer and I can vividly remember getting off this little ferry and being on a quad to the military building and hearing this incredible surround sound of bird song everywhere and thinking this is not what I remember at all. Just a world away really.

Were there things about the landscape that sound and listening revealed to you that were harder to access through your visual practice?

On that second visit I was doing these transect walks. I'm interested in the way sound transitions across the landscape, the way it appears and disappears across scales of time and space. I'd draw these arbitrary lines and record every 100 steps, but I'd also spend a lot more time, especially with hydrophones, popping them in rockpools to hear shrimp snapping, insects stridulating, pondweed popping, sphagnum creaking. Really again with this sense of play but with a sense of inquisitiveness as well, of trying to find an aural window into these nonhuman worlds that are buzzing away at scales vast and tiny that are not usually accessible to our ears.

I also started getting really interested in the possibilities of sonification, in that same spirit of ‘how do I tell stories of change here in ways that are bigger than I can perceive myself right now?’ So I had the MIDI Sprout and would spend time popping it on various bits of vegetation and just sit there with my laptop. I think the one that ended up in the sound work on the film was 20 minutes sat watching the sun go down with this birch tree.

I'd have the laptop set up attached to this birch tree and you could really feel the slowing of the day as the sun went down. All these patterns and silences and rhythms ebbed away as the tree slowed its photosynthesis. You could feel this breathing out, this slowing of the day. And times like that you get this sonic record of a period of time. There's also something quite bodily about it as well, it's like an attunement and an attentiveness that you don't always plan for.

I also went hunting out data sets from researchers and government agencies and got data sets on things like oceanic parameters, surface temperatures, oxygenation, eutrophication and things like that. I essentially thought that with time, if the binaural recordings are recording in seconds, and the MIDI Sprout recordings are recording over tens of minutes, then these longer-term data sets are letting me think and express sonically over 100s or 1000s of years. Using them in the film, it's all part of that accumulation of different speeds and intensities and rhythms of processes on the island and trying to express that both visually and sonically.

Your work has often crossed lines between sound recording and composition. With this project in particular, were you using natural rhythms as compositional starting points?

There was no active composition in this sound work. It was all assemblage as much as composition. It was field recordings, hydrophones, contact mics, the sonifications and the synth granulations. I wanted to assemble them in a way that had this conversation back and forth with the film, and with the written work in the book. I would listen to these quite long sonifications and snip out and use the things that excited me or things that seemed quite interesting or unusual, tonally or melodically. Obviously there was a choice in the tones that I used for the sonifications. I used small synths and marimba and things like that, but the composition was really a process of editing rather than making.

Picking up on the idea of you being open to chance in order to witness changes at different scales within the environment, were there any outcomes or learnings that you took away from the work?

Yeah, that's a good question. I think it really helped me see and communicate this island as somewhere more-than-visual, or more than what it's now been branded as subsequently as tourist attraction. I kept coming back to this phrase of Anna Tsing's in The Mushroom At The End Of The World, where she calls a landscape "a polyphonic assemblage". I always thought that's a really nice way to get at the multiple forms of life, the multiple scales that are all going on in parallel above and below and around us, that shape a landscape. The non-human, the organic, the geological, all these shifts at different paces, different rhythms, different intensities. I hope to have achieved something of that in the work.

Watch and listen to Rob St John’s Örö film and sound recordings here.