The gruesome prehistory of bat echolocation

In the late 18th century, scientists across Europe grappled with myth and mystery to understand how bats navigate in the dark. Their methods bordered on the obscene.

Two-hundred and thirty years ago, biologist Lazzarro Spallanzani was in his laboratory in the city of Pavia in Northern Italy, heating up a piece of metal wire to insert it into the cornea of a live bat. Once he had done so, to the considerable discomfort of the bat, he pulled out the eyeball with a pair of pliers, cut it at the stem and pasted an opaque leather disk in its place. Satisfied that the bat could no longer see, he let it from his grasp, extinguished the candle by which he had been working and watched as it flew with ease between all he had put in its way. “During such flight,” Spallanzani wrote in a letter to fellow scientists in the autumn of 1793, “we observe furthermore that before arriving at the opposite wall, the bat turns and flies back dexterously avoiding the obstacles such as walls, a pole set across its path, the ceiling, the people in the room, and whatever other bodies may have been placed about him in an effort to embarrass him. In short,” Spallanzani concluded, “he shows himself just as clever and expert in his movements in the air as a bat possessing its eyes.”

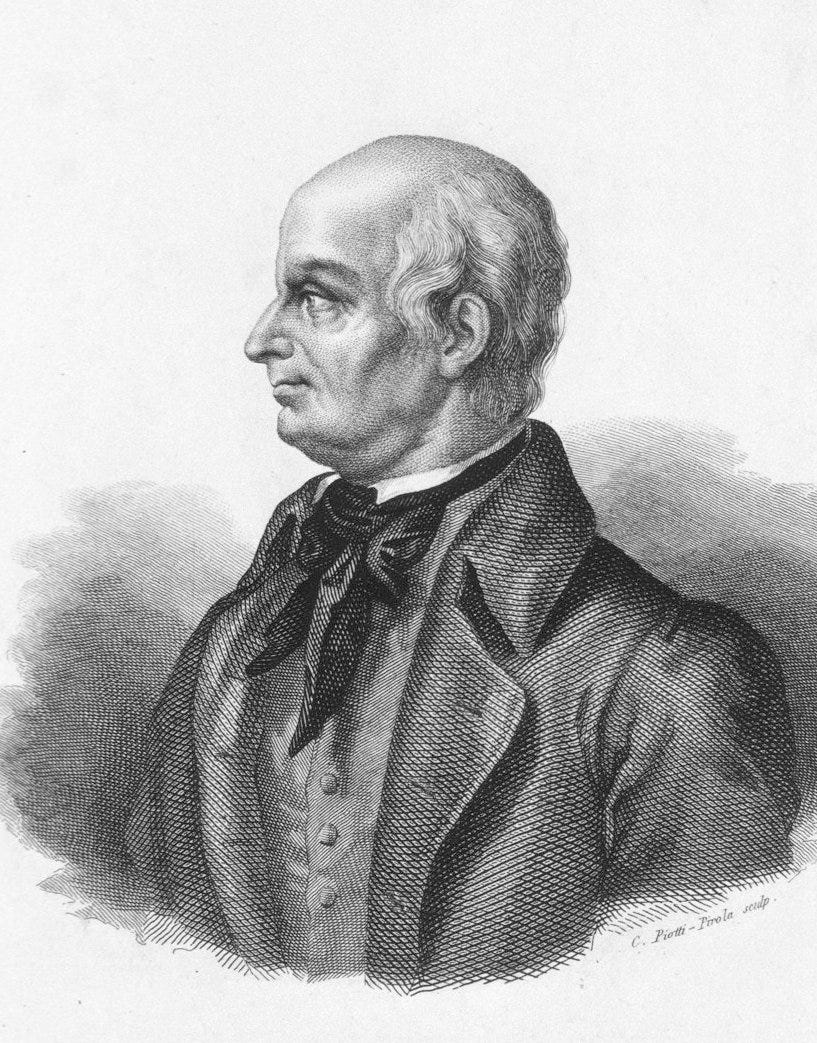

Like many scientists of the era, Lazzaro Spallanzani’s oeuvre was wide and he is remembered now as much for his pioneering research into in vitro fertilisation as he is for determining why stones skim across the surface of the water. He was 64 years old when he turned his attention to bats, fascinated and bemused by these nocturnal primates - as taxonomist Carl Linnaeus had deemed them - and dedicated much of the rest of 1793 to pursuing that which allowed them to navigate in the dark.

In systematic and often brutal fashion, he eliminated one sense at a time, moving from sight to taste by cutting out a bat’s tongue, and then smell by plugging up its nostrils, only to see both experiments have no discernible impact on the bat in flight (other than, he concluded, possibly compromising the bat’s capacity to breathe). If there was a prevailing theory at the time however, it was that bats navigate through touch - sensing changes in air pressure as they flap past solid objects. To rule this out Spallanzani coated one of his test subjects snout to wing in varnish and flour paste. The bat would at first have difficulty flying, he observed, only to regain its vigour and pass all obstacles, including silk threads, that were asked of it. “It is to be noted,” Spallanzani wrote dryly, “that a second or even a third coat of varnish does not hinder the normal flight of the animal.”

When it came to hearing, Spallanzani was also initially sceptical. Having filled the ears of eleven bats with wax, he noted that ten flew unimpaired, convinced that the hearing sense could not be involved since he himself could hear no sound. Baffled, but not beaten, Spallanzani asserted that, having exhausted all five senses, “there is some new organ or sense which we do not have and of which, consequently, we can never have any idea.” If he, Lazzaro Spallanzani could not discover it, then it must be new to everyone.

French naturalist Georges Cuvier was not impressed. Wholeheartedly rejecting the idea of a sixth sense, he published a paper in 1795 advocating instead for the touch hypothesis - that bats navigate through a heightened sensing of the air through which they fly. Such was the strength of Cuvier’s conviction and the weight of his reputation, that the theory was accepted for much of the following century.

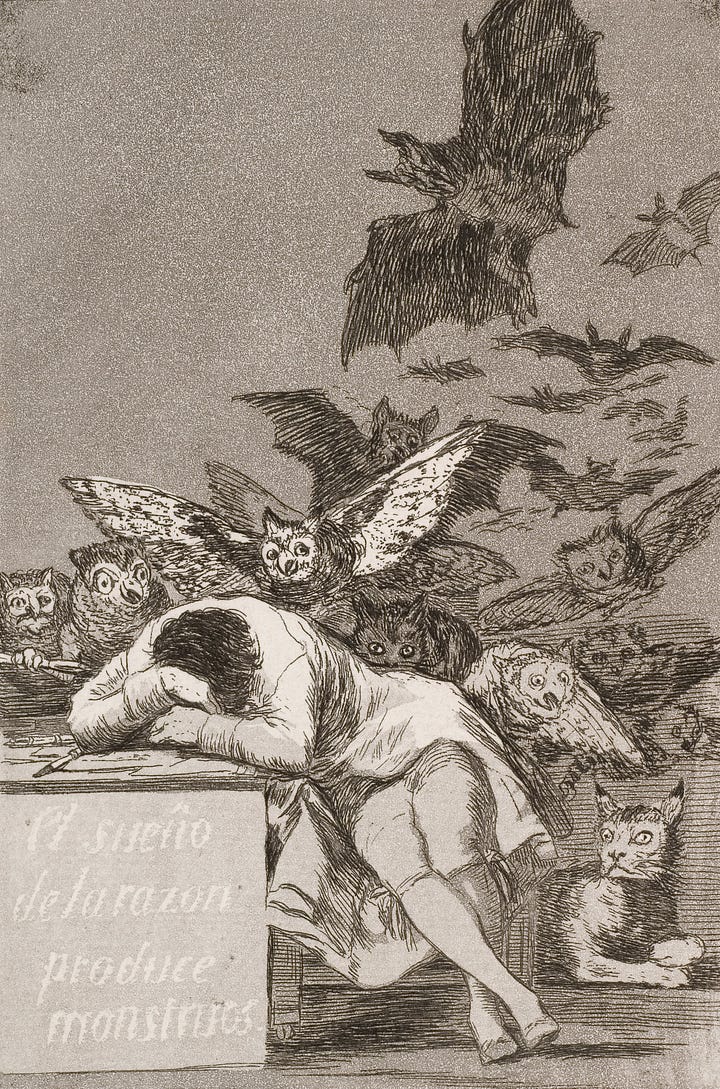

Cuvier’s argument may have been more rational than Spallanzani’s speculative assumption of a sixth sense, but in truth there was little about the study of bats that was not touched by the myths and cultural bias in the Western world which had long painted bats as malevolent, devilish creatures. References to bats as unclean or symbols of the dark can be found in the Old Testament. Medieval paintings of devils were given webbed, bat-like appendages, while the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost was invariably depicted as having pointed wings. Animals of the witching hour, inhabitants of the night, the nocturnal habits of bats aroused the suspicions of Francis Bacon in his 1625 writing Essays and Councils, while it was the hybridity of bird and beast, day and night which animated Comte de Buffon to describe bats as monstrous beings. The climate into which Spallanzani began his bat experiments was hardly one of universal acclaim.

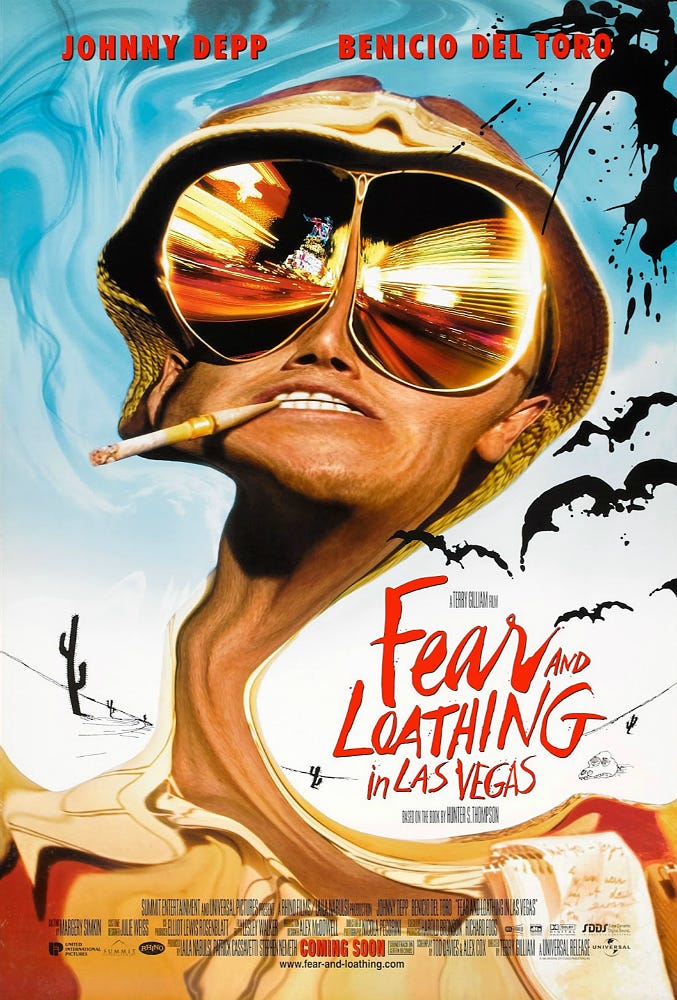

When Dram Stoker imagined Dracula as a villain with vampiric tendencies, the bat suffered another major setback in the cultural imagination, one forever imprinted with the mark of deviance and danger. For when they weren’t preying on the blood of their victims, bats were entering their dreams, symbolic of the onset of madness or depression, harbingers of our darkest fears, as they are in Goya’s painting The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, or in the acid-soaked hallucinations of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The “sixth sense” that Spallanzani bestowed on bats would, two hundred years later, be appropriated by Bruce Willis as a sign of clairvoyance, of communing with the dead.

I remember being touched by D.H. Lawrence’s poems of Birds, Beasts and Flowers as a child, and his vivid descriptions of the bird “flying round the room in insane circles” in fact being “… A bat! / A disgusting bat”. Lawrence was leaning into an image of the bat wrapped in colonial fever dreams of tropical blood-suckers that played into the fears of otherness in the imaginations of Europeans. Accusations that bats might have been responsible for the Covid-19 pandemic have done little to assuage those fears. But as Tessa Laird writes, “it is unwholesome thoughts about bats which indicate the real human maladies: paranoia, hallucination and pathological anthropocentrism.”

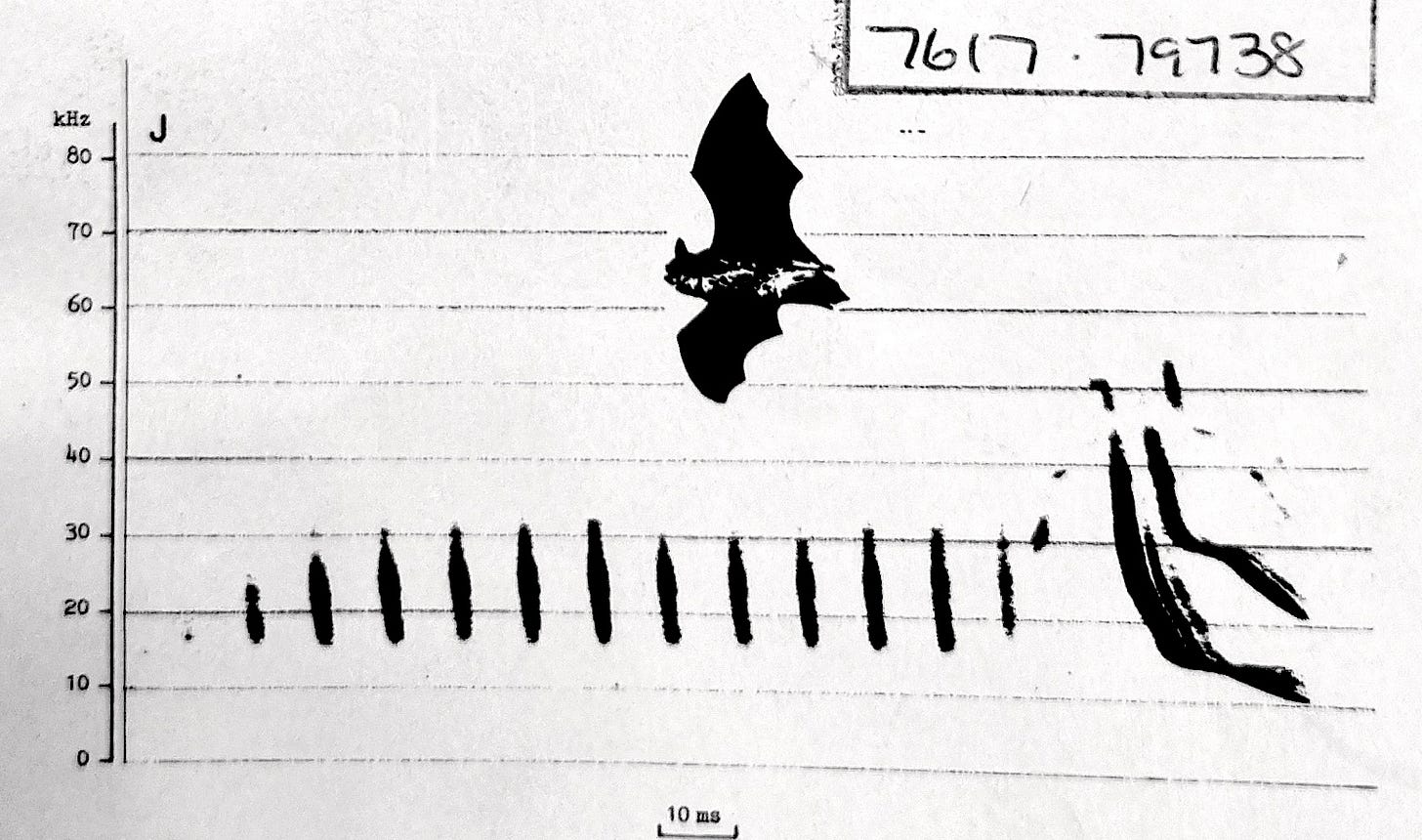

One person who was not willing to accept Spallanzani’s sixth sense hypothesis, nor that of touch proposed by Cuvier, was a Swiss medic and naturalist called Louis Jurine, who had been exposed to Spallanzani’s research and undertook a series of further experiments to test whether it was in fact hearing that played a defining role. Plugging the ears of his bats with turpentine, wax, pomatum and tinder mixed with water, he began to see results that differed from Spallanzani’s own, watching as his bats clattered into one object after another. “The organ of hearing appears to supply that of sight in the discovery of bodies, and to furnish these animals with different sensations to direct their flight, and enable them to avoid those obstacles which may present themselves,” he wrote. Published in 1798, Jurine’s statement became the first clear-cut expression of a theory of bat flight that would, almost 150 years later, be called echolocation.