Uncovering the sonic life of ponds with Action Pyramid

Sound artist Tom Fisher aka Action Pyramid discusses his work with biologist Jack Greenhalgh capturing the vibrant sound worlds of the freshwater pond, one of the UK's most over-looked ecosystems.

The first time I encountered Tom Fisher’s work in person was at an interactive installation of his called We Are All Grazing Limpets. No one was exempt. All present, myself included, had scanned a different QR code to play recordings Fisher had made of these stoical aquatic snails going about their dinner. We sat in silence as the limpets grazed from our smartphones, some chirpier and more engaged, others slower, sadder, perhaps a little more resigned to the routines of their labour.

As with much of Fisher’s sound arts practice, which he pursues under the alias Action Pyramid, it was a quietly unsettling experience, profound and unusual in equal measure. Whether amplifying the skittish strides of a water boatman or honing in on the synth-like drones of the hoverfly, Fisher’s work challenges the hierarchies and assumptions of our anthropocentric world view. As the name of his contribution to BBC Radio 4’s Short Cuts series suggests, his is “an acoustic acclamation to things tiny.”

In an act of what he calls “re-listening”, Fisher hopes an appreciation of these soundscapes will revitalise our conception of over-looked (or under-heard) spaces, from the Hebridean rockpool to the urban arteries of London’s River Lea.

For his latest project, Mardle: Daily Rhythms of a Pond (co-released on Mappa and Skupina in October), Fisher turned his attention to the humble pond, teaming up with freshwater aquatic biologist Jack Greenhalgh to translate the 24-hour sonic cycle of aquatic insect stridulation [the act of producing sound by rubbing two body parts together], plant respiration and photosynthesis into three evocative compositions.

Rooted in Jack Greenhalgh’s sonic research on pond biodiversity, Mardle brings to the surface an ecology of otherworldly rhythms and alien hyper-sounds that feel more like early synth experiments than biological processes. In short, it’s one of the few pieces of music I’ve encountered that really needs to be heard to be believed.

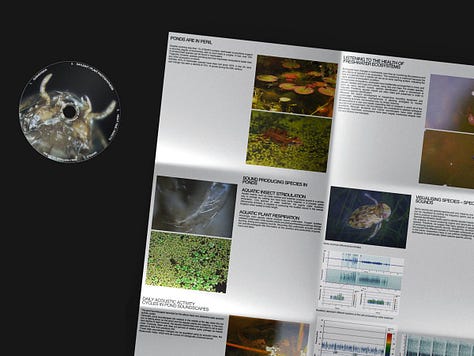

Perhaps most significantly, the work underpinning Mardle represents a breakthrough in our understanding of how life is organised in the UK’s freshwater ponds, which will ultimately contribute to their conservation. “It's so exciting that we've discovered the woodland bird song dawn chorus equivalent for ponds, in the form of nocturnal aquatic insect choruses at night-time, and the whining of aquatic plants as they photosynthesise like busy factories during the midday sun,” Greenhalgh explains.

Never mind the limpets, we are all stridulating water boatmen.

How did you first get into field recording?

Like a lot of sound artists and field recordists I came from a music background. In my late teens I was already messing around with a home computer and production software and got really into electronic music and beat production. I've always been really into sampling, so I started trying to expand my palette of what I was making electronic music with.

I realised quite quickly how amazing it is to have a microphone outside of a studio context, and the complexity and revelations that can come along with field recordings. I've always had an interest in re-listening to environments and using hydrophones or contact mics at different scales. It's a nice way to rethink how we position ourselves as humans in the web of life around us.

Could you expand a little bit on that idea of re-listening to environments?

You can think you've noticed everything, like recognising the sound of a bird, but then realise that there are many layers of paying attention to what it is you're hearing. It’s the classic Pauline Oliveros difference between hearing and listening and thinking about the multitudes of realities you can tune into by listening carefully enough. Using these extended recording techniques [like hydrophones and contacts mics] is another way to interpret that. So you might be listening to what could otherwise be seen as a boring little body of water, but which with these techniques becomes quite mysterious and strange and exciting.

It sounds like this impulse to reassess bodies of water that seem mundane is central to your work.

Yeah, I've always found that quite satisfying. I remember in about 2013 when I was doing my first piece with hydrophone recordings from the River Lea. I presented it to an audience, and I just remember thinking how mad it was that I'd walked up and down that familiar space of the canal hundreds of times, and yet there were all these bizarre sounds I'd found there. I thought it was quite cool that experiences like that can also inspire other people to reconsider their environments. I think a lot of my work tries to convey some of the amazement I have in finding these things.

Your collaboration with biologist Jack Greenhalgh on freshwater ponds feels like the perfect example of re-listening to an environment that is often overlooked and then sharing your sense of wonder in what has been discovered there. How did that come about?

I had been doing a lot of aquatic recordings but had become quite mystified about what I could hear going on under the water. I started reaching out to researchers at UCL and essentially got invited on these field trips to north Norfolk where they were doing farmland pond restoration, and that's how I met Jack [Greenhalgh], who, at the time was starting his dissertation. He was using the sounds that I was recording and thinking about the ponds from a sonic data point of view and how that might be a gauge for levels of biodiversity, which is a fairly new approach to pond surveying in particular.

He has since gone on a bit of a trajectory to do with ecoacoustics in freshwater environments, but for me the album itself was a culmination of quite a few years of recordings, not just from these ponds. It was inspired by this encounter with the research and then from that I took a compositional cue from some discoveries that had been made. For example, there's an acoustic cycle within the pond, a daily rhythm of night and day. I very much take inspiration from the Jana Winderen school of creative approaches to real sonic data. The album is referencing real research but it's also very much a creative interpretation of it.

They’re not all one pond, are they? Are they all based in the UK?

No, exactly. It's many ponds into one imaginary pond. They’re mostly in Norfolk and in various freshwater locations around London and Bristol. There are one or two miscellaneous water bugs from somewhere else, though I can't quite remember where!

How does this creative interpretation of a pond’s daily cycle play out across the album’s three tracks?

At the beginning you're above the water and you’ve got the dawn chorus, and then as you're submerged into this completely mysterious world, you start to get these inklings of what's happening. Interestingly, dawn can be a bit of a quiet time. We found that, in some ponds at least, the solar noon and the middle of the night are the most acoustically active points of the day. The idea was to illustrate that with this gradual building towards the middle of the plant-focussed daytime piece, which culminates in intense activity. And then there’s a slow shift, there's a bit of lull and then you get this great chorus of insects which comes later in the album that illustrates the night.

I also wanted it to have a cyclical feeling. As the piece fades right at the end there's rain which alludes to the water cycle and the reasons ponds exist at all. And then you come up above the surface again. You've got early morning rain and you've got the hint of a robin singing, and the hint of the dawn chorus again, so it could theoretically play as a loop.

What is Mardle a reference to?

That's another little nod to the origins of the project. It's an East Anglian word for a small pond. I think it also means to chatter, which is perhaps linked to the fact that human life would have been centred around small ponds in that landscape in the past. It's quite an interesting etymological link.

The underwater recordings really sound like wild chattering, albeit somewhat alien. It doesn't sound like it could possibly come from a pond at all.

Yeah, I think a lot of my work is about that. It's about trying to get rid of that hierarchy of “this is just a boring pond and I'm a really clever human, and I think I know everything about what's surrounding me.” I like bringing that into question with these little audio discoveries and then put them on a bit of a pedestal.

What is it that we are actually listening to?

The main things you’re hearing once we get submerged after a few minutes are aquatic insects, mainly water boatmen and a few other species of water beetle. Then you’ve got this fizzing, whirring, buzzing sound, which is essentially when the oxygen level in the water rises to the point where the plants can’t just dissolve it, so it starts to make these really miniscule bubbles, depending on the pressure and the metabolism of the plant and lots of things that are not really understood yet. It's like cavitation essentially, which creates these pulses of sound. When the pulses become close enough together they start to create tones. It's a bit like playing with a Square Wave Synth. When it's at a very low frequency it's just like bup bup bup bup bup, and when you ramp it up it sort of goes bupbababababababeeeeee. That’s principle, but with bubbles.

Is there any sense that the underwater world reacts to the sound as well as just creating them? Do these sounds have a biological function?

I think that's completely unknown really. It blows my mind that there are ponds everywhere and yet there's so much stuff that no-one really knows. With the insects there is clearly a biological function relating to mating and territory, but the sound types have yet to be fully categorized to a species-specific level.

I also think there have been studies showing that plants react to the sound of running water, but I don’t know about reacting to the sound of themselves, and also I don't know about whether fish would be attracted to certain sonic things under the water for whatever reason they might need. There have been studies done in the oceanic field with reef sounds attracting other creatures, but it's pretty mysterious in that regard.

In that sense, it still feels crucial that the project is grounded in scientific research.

Yeah, I was quite keen to get that across and keep it in the liner notes. It's illustrating some research, showing the limits of what we know and showcasing it in a way that is demonstrating how strange and misunderstood it is.

What are you hopes for the album once it’s out? A role in conservation conversations or as a musical work or somewhere between the two?

I always really like it when things are showcased outside of the niche sound art world. It can be a really great way to engage people, capture people's attention and highlight these fragile and maligned habitats.

You mentioned sound artist Jana Winderen earlier. Were there any other inspirations you were thinking about while working on Mardle?

When I’ve played it live, there are some very subtle extraneous hyper-frequency elements that I like. They're the only things that have been slightly added to give a bit of a bed to these real, textural sounds and sometimes people have said, “I can tell you listen to sound-system music”. I think there's something about the slightly wild top end and then this bed beneath it which resonate when you hear it really loud. It's an interesting comment someone made, and I do connect to it. The distant King Tubby reference in there!

Did you have any particular epiphanies while you were recording?

I think the plant sounds are still quite hard for me to wrap my head around. We know plants are alive but to consider their living presence with direct sonic evidence can be quite profound. I’ve literally had it where I've been recording a patch of hornwort in the River Lea, and I could hear it changing as clouds were coming over. I could hear the environment affecting the plant directly. It’s in those moments where I think I can’t believe I'm listening to this.

Mardle: Daily Rhythms of a Pond is out now on Mappa / Skupina